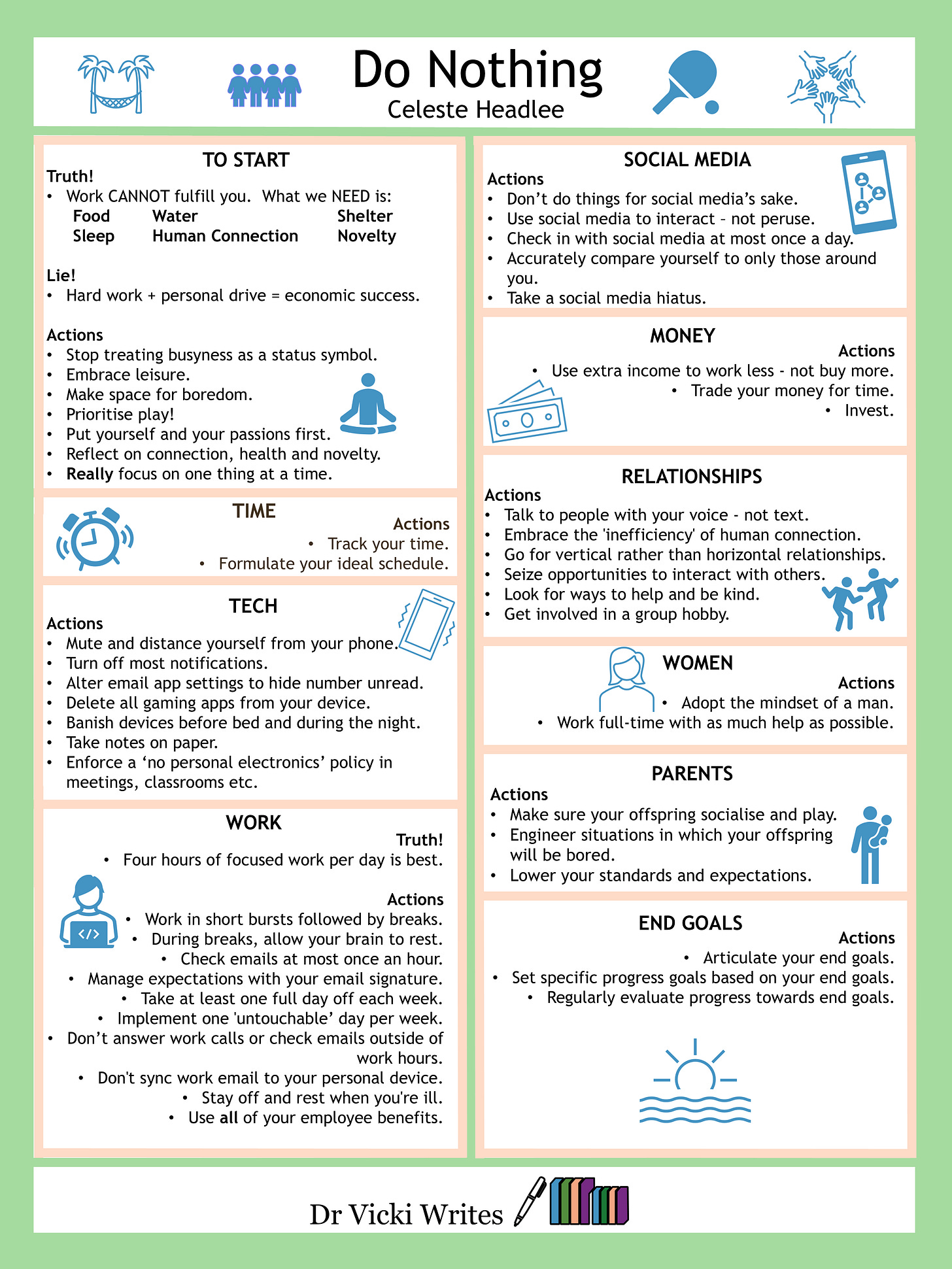

Do Nothing by Celeste Headlee: To Start

A Self-Help Summary

I first read this book in autumn 2020. In it, author Celeste Headlee urges readers to slow down, stop rushing frantically through life, and turn their attention back towards what is truly meaningful. She explains why so many of us are self-proclaimed workaholics nowadays, why we must redirect our focus onto building and sustaining intimate relationships, and why truly restorative leisure is vital to our humanity. She gently and convincingly argues that real contentment will only be within our reach if we start prioritising our health, passions, dreams and community over desperately trying to increase our income. She also presents the reasons so many of us feel harried all the time – a great deal of which relate to our use of our devices. Over half of the Work actions are only really applicable to those who have some autonomy over how they spend their working hours and can, to some extent, control the number they put in, as well as whose jobs are heavy on email. Nonetheless, I am in no doubt that almost everyone would benefit from reading what Celeste has to say. To hear her talking about it herself, see episode 152 of the Best of Both Worlds podcast.

To get the most out of these lessons I have distilled in the form of a Self-Help Summary, I recommend reading over them, then, if they resonate with you, buying and reading the book. This is the best way to cement the author’s teachings in your mind, and boost your chances of applying them to your daily life.

TO START

1 Work CANNOT fulfil you. What we NEED is:

Food

Water

Shelter

Sleep

Human Connection

Novelty

The vast majority of us do have to work to attain those first three needs, and I would argue the fourth too, since sleeping without adequate, safe shelter or a full belly is not a situation anyone wants to be in. However, we have lost sight of these reasons to work, and are now prioritising it over our last two needs – human connection and novelty. Novelty is necessary for a fulfilling life because it makes time seem longer by helping us form clear, vivid memories we can look back on. We have evolved to need human connection, as in ancient times we would not have survived on our own.

Even in these modern times, neglecting our social lives in favour of work and achievement may still be deadly, though. An extremely large, long-running study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology in 2019 found that people who were either not married, had less than seven close friends or relatives, or did not regularly (at least once a month) attend religious services or take part in clubs or group activities, were significantly more likely to die young, including from cancer and cardiovascular disease. We need to start prioritising friends and family over work.

If you are struggling with loneliness and feel bereft of closeness in your personal life, start by identifying all the relationships you do have that you could try to develop and strengthen. Think about your passions and brainstorm where you might find others who share them. You may need to tackle personal issues first, too, such as social anxiety. The bottom line is, whatever you do, don’t give in to the temptation to bury your head in the sand by putting more energy into your work.

2 Hard work + personal drive = economic success.

The culture we live in has convinced us that giving our all to our jobs is the optimum way to live. We believe that in doing so, we will eventually become rich and revered, which will ultimately make us truly content. If this was true, though, why would the income gap in so many countries be so vast? There are countless motivated, conscientious people born into poverty, so wouldn’t it have shrunk by now if it was? In reality, only 1% of Americans are likely to become millionaires, and those who work more than 50 hours a week only earn 6% more than those who don’t. Believing we can achieve illustrious success purely through our own efforts is dangerous. It convinces us to work harder even when we aren’t seeing immediate results. It can blinker us into working at the expense of our health, personal interests and relationships. What’s worse, it’s a form of mass delusion that stops us questioning the status quo and fighting for economic and political policies that would benefit those in lower income brackets.

3 Stop treating busyness as a status symbol.

A century ago, idleness was what signified wealth and stature. Since then, we have come to believe that the busier someone is, the more important they are, or the more respect they should garner, because it obviously means they are very hard working. As a result, many of us go on about how packed our schedule is, and how we ‘literally’ have ‘no free time’. We may genuinely believe it too, but in a way we also use this storyline to elevate ourselves – I know I did. If you are genuinely extremely busy and stressed, ask for help instead of giving off the air that you are proud of how manic your life has become. Rushing around, splitting your attention between multiple things at once is potentially damaging your health and relationships.

4 Embrace leisure.

Comfort and leisure time are basic human rights, and yet many of us feel that we have to work a crazy number of hours, or complete a certain number of tasks, in order to earn them. Some of us cannot even sit down with our families without feeling antsy and guilt-ridden until we’ve replied to all of our emails or completed all of the ironing. However, there will always be more emails to read and ironing to do, while we can never reclaim time lost with our loved ones. Leisure, as Celeste defines it, is not sitting on the sofa for hours on end mindlessly watching TV. It is consciously choosing to sit down for an hour to avidly watch your favourite show, relaxing on your porch watching the world go by, strolling around your neighbourhood, painting, playing catch… Doing something for pure pleasure’s sake, as opposed to doing something with the aim of making money or adding to your list of accomplishments. This form of leisure is necessary for our brains to function at full capacity. It boosts our productivity, creativity and insight; it can also strengthen our immune system. The Italians clearly get it – their phrase il dolce far niente, brought into the spotlight by Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat Pray Love, means ‘the sweetness of doing nothing’.

5 Make space for boredom.

Smartphones have almost eradicated boredom from our lives. Now, when standing in a queue or folding laundry, we can whip them out and browse, read and respond to emails, get things ticked off our to-do list, or simply put on a podcast. That’s not always a bad thing, but our brains need to be bored from time to time so that they can reflect and process – our insight, imagination and ability to learn depend on it. Start by trying to notice when you begin to feel bored and stop yourself from using a distraction, such as your phone, when you do. If you can’t bear complete silence, listen to music: it still allows the brain to idle and process as it would if you were in silence, unlike listening to a podcast, book, or discussion of some kind. You could then go a step further by scheduling in time to be bored – say 15 minutes or so a week.

6 Prioritise play!

I first came across the concept of adult play a few years ago when I was looking for ways to recover from PhD burnout and found Charlie Hoehn’s Play It Away: A Workaholic’s Cure for Anxiety. Play is a special form of leisure – leisure that is specifically fun (for you: others don’t have to agree). Think something you would have done as a child, voluntarily, for fun, when you weren’t allowed screen time; Charlie calls these Play History activities. His top five were: 1) creating art; 2) trying to make people laugh; 3) practicing guitar; 4) playing sports; and 5) trying to build or fix things. I spent a while thinking about what mine were and came up with (in no particular order): 1) reading books and magazines; 2) making and sometimes memorising lists then getting people to test me on my recitation skills; 3) organising things like my auntie’s shoes and dad’s CD collection; 4) drawing and painting; and 5) dressing up paper dolls. While solo-play is definitely better than no play at all, Charlie notes that in his experience, the most stress-busting play is that which is active, takes place outside, and involves others, like a game of rounders in the park with friends. His book is chock-full of ideas for all kinds of play, though.

Celeste states that playing in this way helps us to be more efficient, manage stress, and create trust, which is probably why some companies corral their workers into taking part in team building away days. She urges people to stop trying to turn their much-loved hobbies into side hustles and remember that their purpose is to provide pleasure and time out from the stresses and strains of daily life.

Charlie recommends incorporating 30 minutes of play into each day but, as with boredom, I’d say scheduling in even 30 minutes a week is a good place to start. Think about the upcoming weekend and how you could fit in some time to simply play.

7 Put yourself and your passions first.

Ultimately, no one cares about you as much as you (and possibly your parents) do. That’s why taking a chance on yourself is more likely to pay off in the long run than slogging away day and night for someone else. My brother, for example, committed himself to learning all there was to know about body building and personal fitness while he was still at high school. He was simply compelled to do so; he had no plan to make money from it at that time. He carried on for over a decade while working full-time, and eventually built up enough of a reputation as a fitness coach that he was able to leave his job and go out on his own. He now makes around the same as he would have done if he’d worked at his job for another, say, 20 to 25 years.

I’m not saying that kind of outcome will materialise for everyone: I’ve been working on writing for the past five or so years and have no hope of making a penny from it anytime soon. I did in the beginning, but I’ve realised I need to do it regardless, because it fulfils me. Don’t confuse this with turning your hobby into a side hustle as vehemently discouraged in Action 6 – I spend hours writing and almost no time figuring out how it could be profitable, and that’s the way it should be. I write because I love it, not because I hope it will make me six figures.

Strategise how you could put in less effort at your day job to devote more of your time and energy to your dreams; it’s unlikely anyone will even notice if you start slacking off a bit. I highly recommend listening to episode 3 of Danielle LaPorte’s Light Work podcast The service of joy, especially in these times, for encouragement and inspiration.

8 Reflect on connection, health and novelty.

When you’re finally sitting down at night reflecting on how your day went, instead of asking yourself “How many tasks did I tick off my to-do list today?”, ask yourself things like: “How did I add positivity to another’s day?”; “How did I care for my mind and body?”; “Did I learn or try anything new?”; and “Did I do or experience anything out of the ordinary?”. I’ve changed the way I journal: now, instead of simply writing out a brief summary of my day, I write under the headings Positivity and Connection, Mind and Body, and Novelty. #Under Positivity and Connection I put things like “Chatted to my parents on the phone”; under Mind and Body “Ate a nectarine and walked outside for half an hour”; and under Novelty something like “Watched my first Amanda’s Favourites video on YouTube”. It’s those kind of things that make a meaningful and fulfilling life, not mega-efficiency.

9 Really focus on one thing at a time.

We have a tendency to try to do multiple things at once, or to frequently switch back and forth between different tasks. We think this will help us get more done, but in actual fact it wears our brains out making us less productive. It also has long-term consequences - if we try to multitask often, our cognitive processes (i.e., deep thinking, critical thinking, problem-solving) eventually become compromised. As such, Celeste recommends allocating specific portions of time to specific tasks – at home and at work - during which we strive to shield ourselves from distractions. Arguably, the worst disrupters we have to protect ourselves against are our devices, social media, and email. Upcoming actions cover exactly how that can be done in practice.